Front Reflection and Side Reflection

Seitu Ken Jones, 2025

Lithograph on Rives BFK White paper

Edition of 7

Image: 33 ½ x 25 ½ inches

Paper: 40 ½ x 32 inches

Click here for availability or Email our Gallery Director Alex Blaisdell alex@highpointprintmaking.org

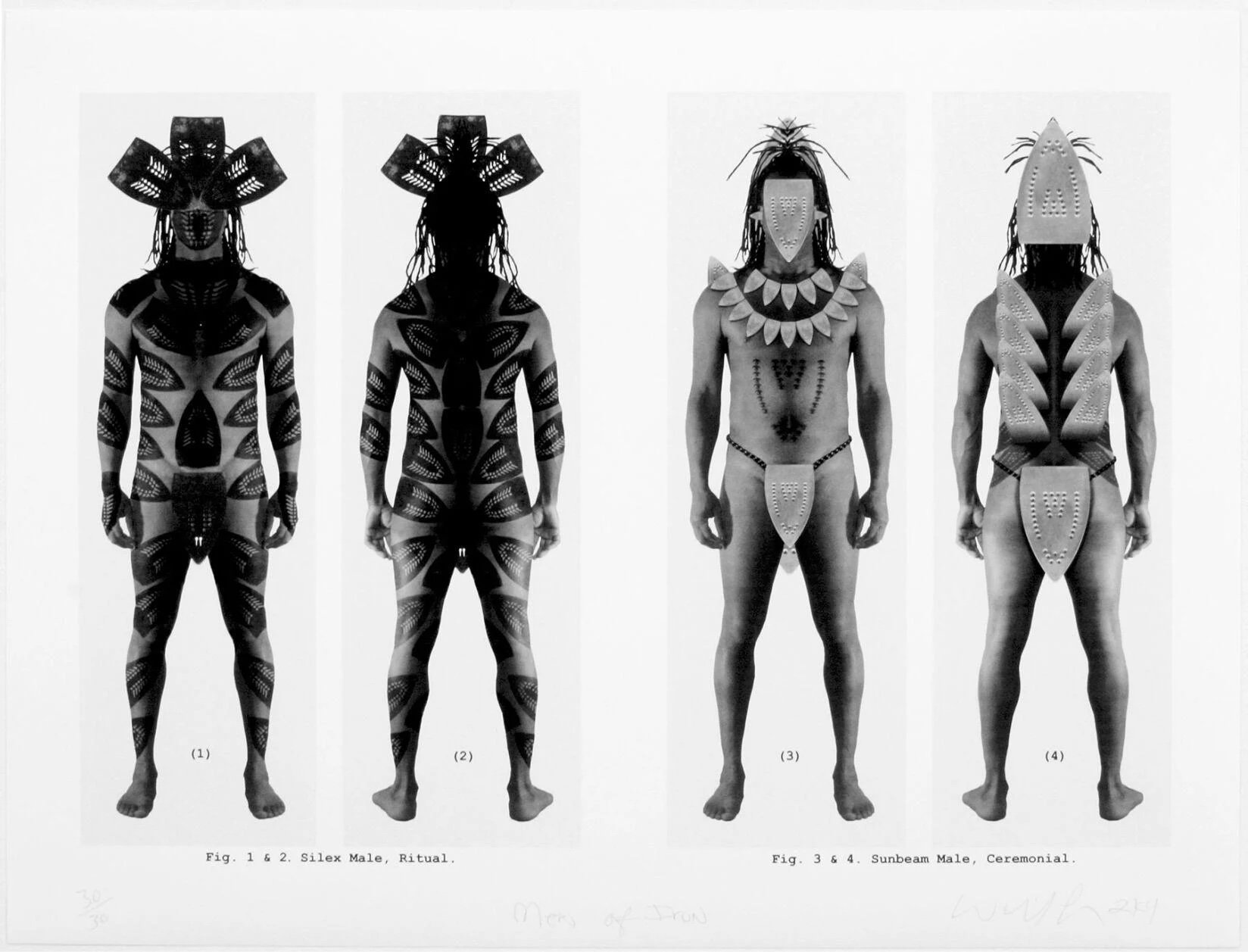

Highpoint Editions is pleased to release Front Reflection and Side Reflection, two new lithographs by Minnesota-based artist Seitu Ken Jones. Inspired by the Zealy Daguerreotypes, these prints are Jones’s first with Highpoint Editions and exemplify a fierce dignity and resilience in response to a troubled history and continued adversity.

About Front Reflection and Side Reflection

Source imagery including an image of one of the Zealy Daguerreotypes and an image of the artist’s Great Grandfather.

In 1976, a set of photographs from 1850 was discovered in a Harvard University storeroom. The daguerreotypes were commissioned by Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz, who was an adherent of “scientific racism”, to prove the inferiority of Black people. The photographs were taken by Joseph T. Zealy and are now known as the Zealy Daguerreotypes. The seven subjects of the photographs were enslaved Africans who lived in South Carolina, and were posed in both clothed and nude positions.

For the last 10 years, Seitu Ken Jones has painted and created a series of self-portraits that recall the experiences of African American men over the last 400 years. Inspired by the Zealy Daguerreotypes, Seitu’s prints mirror the degrading and disturbing images captured by the photographer. “Each daguerreotype reveals an individual, deeply dignified and expressive. Their hurt, contempt, fatigue, utter refusal are unequivocal,” says Parul Sehgal of the original images.1 In each of Seitu’s self-portraits, he reveals himself in the most dignified and resilient manner of those whom he honors. Jones places himself as the subject and the documentarian, recontextualizing the images as a symbol of humanity, history, and a continued fight for freedom and liberty.

Detail of Front Reflection

Assistant Printer Brian Wagner preparing the stone for Side Reflection

Each layer of the 7-run lithograph calls attention to the process. The outer borders mimic the irregular edges of the lithographic stones the artist drew on to create the portraits. While the coloring of the background can also be viewed as referencing the sepia tones of an aged daguerreotype, each layer is an homage to the materials used in processing lithographic stones. The layers of brown were matched to both the liquid asphaltum used before inking the stone, and the color of the stone after a thin layer of gum arabic has been buffed in to preserve the image. The transparent grey layer that makes up the background echoes the cool grey of the lithographic stone. The black of the lithographic crayon drawing is also iconic to the lithographic process and legacy; furthering these prints’ place as a contemporary reflection of historical statements and processes.

Lead Printer-in-Residence Judith Baumann and Assistant Printer Brian Wagner printing one of the layers of Front Reflection.

Earlier proofs of Front Reflection and Side Reflection in the studio.

Seitu Ken Jones signing Side Reflection on May 6th, 2025

Seitu Ken Jones (b. 1951) is a Saint Paul, Minnesota based artist whose interdisciplinary practice works to restore our Beloved communities by blending art, food, conversation and beauty. Working on his own or in collaboration, Jones has created over 40 large-scale public art works. He's been awarded a Minnesota State Arts Board Fellowship, a McKnight Visual Artist Fellowship, a Bush Artist Fellowship, a Bush Leadership Fellowship, and a National Endowment for the Arts - Theater Communication Group Designer Fellowship. Seitu was awarded a Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and was the Artist-in-Residence in the Harvard Ceramics Program. He was Millennium Artist-in-Residence for 651 Arts in Brooklyn, NY, and was the first Artist-in-Residence for the City of Minneapolis. In 2014, he integrated artwork into three key stations for the Greenline Light Rail Transit in the Twin Cities.

A 2013 Joyce Award, from Chicago's Joyce Foundation allowed Seitu to develop CREATE: the Community Meal, a dinner for 2,000 people at a table a half a mile long. The project focused on access to healthy food and community conversation. Beyond art making, Seitu worked with members of his neighborhood to create Frogtown Farm, a 5-acre farm in the heart of the City of Saint Paul. He is the recipient of the 2017 Distinguished Artist Award from the McKnight Foundation. His 2017 HeARTside Community Meal in Grand Rapids, MI was awarded the Grand Juried Prize for ArtPrize Nine. A retired faculty member of Goddard College in Port Townsend, WA. Seitu has a BS in Landscape Design and an MLS in Environmental History from the University of Minnesota.

For availability and to purchase Front Reflection and Side Reflection, email our Gallery Director Alex Blaisdell alex@highpointprintmaking.org